When to promote people

Setting a straightforward philosophy to demystify promotions

Hi and welcome to the latest edition of Rough Terrain. Apologies for the minor break in publishing my dear, loyal, 42-strong readers! Work and life has been busy. But this newsletter is a cathartic release as well as a useful tool for clarifying my thoughts (a serendipity engine, if I dare say so). So I persist!

This article’s referral is Alongside. Alongside launched a crypto index fund, allowing its customers to get exposure on a basket of blue-chip crypto coins (think of the S&P 500 index fund but for crypto). Instead of having to do the research yourself to learn which coins are worth investing in (a full time job that I can’t possibly attempt), Alongside does it programmatically for you. This is the passive investing in web3 I’ve been looking for!

Rapid Fire

Stuff I find interesting (and hopefully you do too!)

In my article about setting goals, I touched on the toxic behavior of teams who intentionally set their goals too conservatively. This is often the result of bad leaders who traumatized their people, punishing them for not meeting aggressive goals. These people learn to “sandbag” their goal setting so they’re always hitting their targets. Which sucks, because then you’ve got teams who are intentionally not swinging for the fences and boom, there goes your product and company strategy. This article is a good compliment to mine, check it out!

I saw this tweet and had to lol. I was such a Star Trek nerd growing up (Next Generation of course, get the f outta here with that Kirk nonsense). I had a giant collection of action figures that instead of playing with, I kept in their boxes and pinned to my bedroom wall like some kind of display case. I know, I cringe when I read this too… But this tweet made me realize that I actually DO understand all the people collecting NFTs right now:

Speaking of NFTs, this thread does a great job opening your eyes on all the possibilities of that technology. My article about Bacon helped me understand how a NFT could tokenize a document like a lien on a house. But we’re just getting started! Check it out:

MORE NFT TWEETZZZZ:

Okay, last tweet, but worth it, your mind will blow. In August 2020, some folks made a crypto coin call Shibu. It had no value whatsoever, it was a joke. But jokes are kind of what’s running the economy right now (Tesla, GameStop, etc.) Somebody bought $8K worth of Shibu, which was 10% of the total market at that time. God knows why. Fast forward 400 days and the Shibu joke has kept being funny and therefore kept increasing in value (because capitalism???). Each coin is still a fraction of a cent, but when you’re dealing with millions and millions of coins each worth a fraction and that fraction becomes a bigger fraction….profit! The person who bought $8K of a joke crypto coin now has $5.7 BILLION of a joke crypto coin. Re-read that last sentence and question what it is you’re doing with your life. This is probably the greatest return on investment of all time. Now the question is, how do they actually get all that money? Can’t pull out your 5.7 billion without tanking the market of Shibu, which is completely made up in the first place. Rich people problems, am I right? The world is insane.

When to Promote People

We’re approaching the end of the year, which means it is time for annual performance reviews and promotions. Which means it’s also time for every people manager to hate their life as they spend hours and hours writing those performance reviews and promotion cases on top of all the regular work they have to do. Both of these things are immensely important. People work hard all year (or longer) and reviews and promotions are, for better or worse, how they get their just rewards in exchange for that work.

Most discussions between the person under consideration for promotion and their manager goes like this:

Employee: Do you think I can be promoted?

Manager: [squirming in their seat, looking for emergency exit door] well, it depends on how Q4 results of the company and if our budget is approved and if Mercury is in retrograde…

It’s not fun for anyone. Employees are hungry for certainty on their career progression. Managers are hungry for stability and performance of the team. Instead of this typical conversation, which results from the employee not having a strong grasp of what it takes to get promoted and the manager not helping them understand (or even knowing themselves), we should be having conversations like this:

Employee: I’ve collected all the big wins and key results from my work in the past year and arrayed them across the areas that our organization uses to assess performance and promotion potential. I know that I’m strong in most areas while also having some growth opportunities in a few remaining areas. I’m fairly confident that I’m ready for promotion, but of course you may have different interpretations of some of my work as well as a better understanding of how the organization is calibrating performance standards at the next level. Can we review this spreadsheet I’ve made of all my work?

Manager: [star-struck, tears forming in their eyes] please never leave me

Determining when to promote people doesn’t have to be rocket science or requiring the use of a Ouija board. It does require that the organization has a well articulated promotion philosophy and has done its preparation by setting standards and helping everyone know what those standards are. It’s damn important, so let’s do it right!

Past Lives

My own promotion experiences have led me to develop a philosophy around promotions.

In the Army, the promotion process is very mechanical, as you might suspect. It’s almost conveyor-belt like. You do the job you’re assigned and after the required amount of time, you get promoted (barring any major performance issues). The superstars can move up a bit faster, and the turds move a bit slower. But the vast majority are fairly formulaic. When I was promoted to Captain (and later to Major) I jokingly thanked the Army for the deep honor of my automatic promotion.

Amazon was a very different experience. That was a bloodbath (as many things Amazon-related are). At Amazon, you have to “serve in role” for a year before you get promoted. This is done so Amazon can see if you can successfully perform at the next level and only after proving yourself for a year do you get promoted. This is a fantastic deal for Amazon and absolute shit for the employee. Amazon gets a year’s worth of work from the employee at a pay rate one level lower than the work they’re doing. They also massively derisk chances of promoting incompetent folks by getting to observe how they perform at the next level for an extended period of time. Great deal for Amazon! Meanwhile, the employee gets screwed. They work their ass off performing at the expectations set for a level above their current one without getting paid appropriately and with no guarantee they’ll get promoted at the end of this trial period. Lame.

Speaking from my personal experience, it sucked. It felt like I was under a microscope. I always worried about the VPs and Directors I occasionally interacted with who could sink my promotion with a single raised eyebrow. When I was promoted, it wasn’t a big celebration, it was more like release from an extended torture session. Not a psychologically safe promotion process, huh?

Amazon gets away with this because it’s Amazon. It’s brand and wealth helps it attract top tier talent across the world and that talent endures the promotion process because of the value of having Amazon on their resume. I don’t think this will last forever, as the nature of work is rapidly shifting in favor of the employee (more on this in a future article).

WeWork was the polar opposite of Amazon (as many things WeWork-related are). Promotions were correlated to how much weed one smoked with the CEO. Joking! Kinda? WeWork suffered from the pains hypergrowth companies have - rapid promotions of early employees who end up going past their competence ceiling (Peter Principle). For some folks, being an early employee is incredible precisely because of this effect. A mid-20-year-old can go from entry level IC to Senior Manager or Director in a few years time and so long as you’re actually capable of moderately performing at those levels, you’ve just gotten fast tracked in the eyes of corporate America. But at WeWork, hypergrowth combined with massive nepotism, resulting in slack-jawed mouth breathers who were VPs and Senior Directors. Where Amazon promotions are all rigor and excessive diligence, WeWork was YOLO and Fuck It, Let’s Do It Live.

Surely there’s a happy medium between the two?

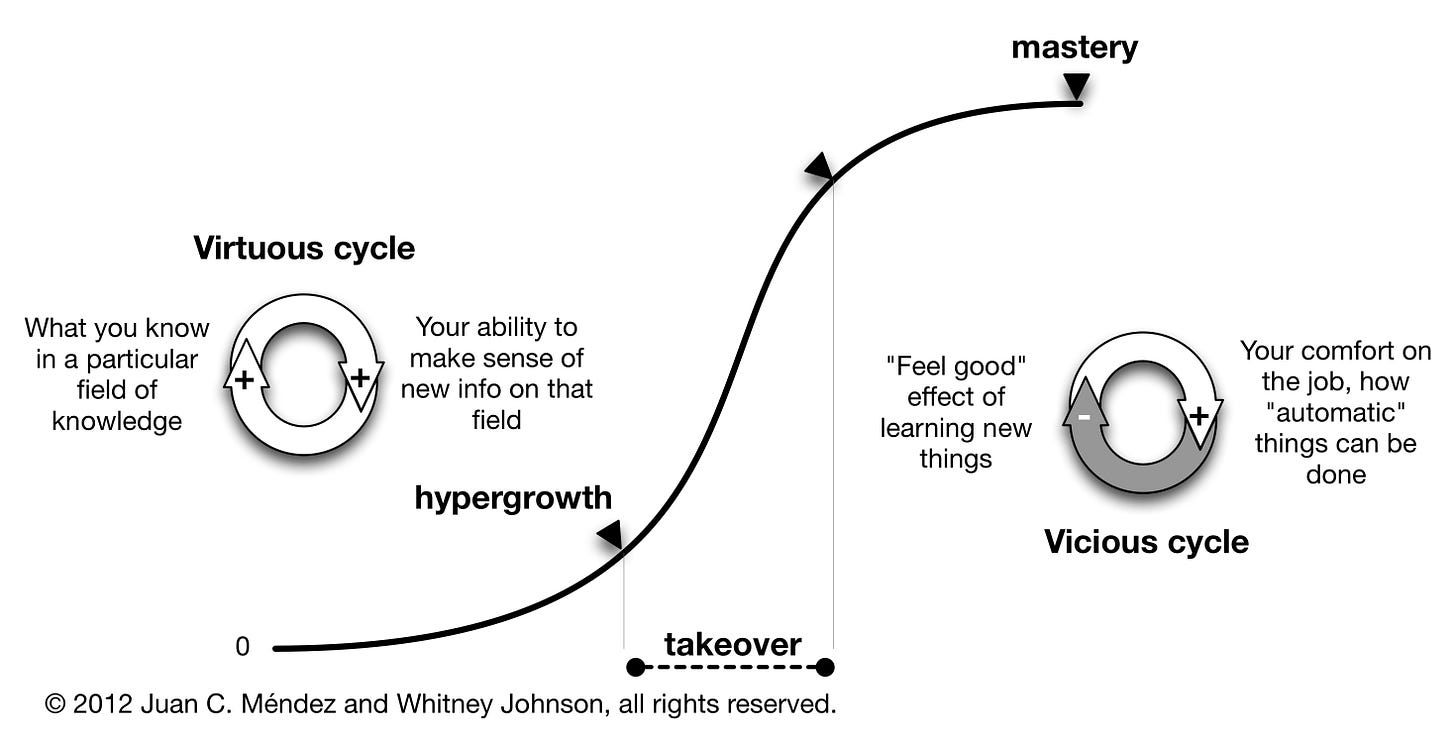

The S-Curve of Personal Development

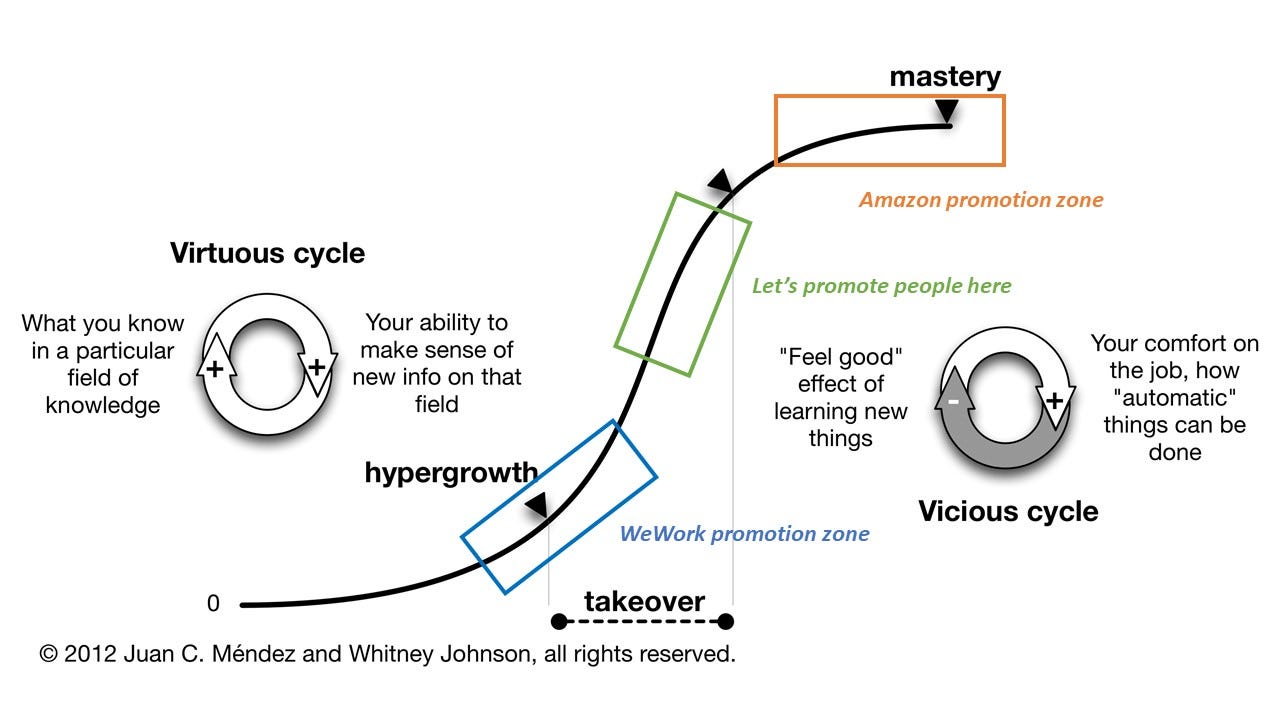

You may or may not be familiar with the S-Curve (aka Sigmoid Function). It’s a commonly used model for explaining the acceleration of one’s performance in a subject over time. You start small, barely knowing what you’re doing, get increasingly better over time, then eventually top out as you achieve mastery. Really good HBR article by Whitney Johnson and Juan Carlos Mendez-Garcia that I’ll cite if you want to read more.

We all go through this S-curve constantly. Can you ride a bike? If yes, you went through the S-curve. I bet you sucked at it and fell over a lot when starting. Then you learned how to balance and got off training wheels. Then you started going faster, going over roots and rocks, down steep hills, etc. Then you topped out at a level of mastery (mastery being relative - perhaps you only need to casually bike around town or perhaps you’re Danny McCaskill). The S-curve is a fairly universal model for performance at a thing over time, whether it’s a person or a group of people.

Holds true for your performance in your job. When you start a new job (either at a new company or a new role in an existing company), you’re at a relative level of amateurism. You don’t know how to be great yet. Either because it’s the first time at this level of responsibility (newly promoted), new job type (switching roles), new domain/industry (switching companies), or other. So you start climbing the curve, acquiring knowledge and skills. Deliberate practice of your job’s responsibilities gives you the repetitions to speed up the virtuous cycle of learning. The more you do, the better you become. Strength follows strength. Things start getting easier so you can do more things and the things you used to struggle doing can now get done at a fraction of the cost/time. In other words, you’re now good at your job! But eventually, it gets hard to get better because you’re already pretty good. The time and effort it takes to go from 20% to 80% is equal to the time and effort it takes to go from 80% to 90%. This is mastery, where small margins of expertise determine who is the GOAT from who is really really good but not the best.

We’re all going through many S-curves. I have a S-curve as a product leader. A S-curve as a husband. As a father. As a telemark skier. And so on. The challenge as it relates to promotions in a corporate setting is matching the needs of the company with the point on the S-curve the employee is at.

The Sweet Spot

I think both Amazon and WeWork did it wrong. Amazon waits for you to be at or near the top of the S-curve. To get promoted there, I had to be so good that not only was I a master in my current position, I also proved my worth at the next level. WeWork found warm bodies and promoted them before they were ready (bottom of the S-curve). Doesn’t take a genius to realize that we can probably do something in the middle.

Here’s the philosophy to follow - promote people when they’re mostly ready. Don’t wait until they’ve checked every box on the S-curve at their current position like Amazon does. Nor should you promote just when they’re starting to show good performance like WeWork did. Promote when they’re good going on great instead of great going on perfect or okay going on good.

How do you know if they’re mostly ready? There’s where the real work is. You need standards and expectations for every role. What “right looks like” needs to be clearly documented and rigorously reviewed. This is responsibility of senior leadership such as the heads of each job function (product, design, engineer, sales, etc.) In addition, it’s the responsibility of the seniors leaders of each of those job functions that report to the head of the function to help them build and maintain those standards. This is the rubric used to examine the performance of an individual. It should be treated like a sacred document. There are few artifacts more important.

Suppose your performance standards document identifies five key areas that each member of the organization gets evaluated against. Things like “results delivered”, “peer and organizational leadership”, and so on. Each level needs its own interpretation of what right looks like for each area. What you expect of an entry level IC for “results delivered” should be radically different than what you expect of a senior manager. You have to sweat the details here, it’s crucial. You can’t phone it in and say that a senior manager is expected to deliver more results than an IC.

Evaluating someone for performance and/or promotion becomes much easier now that you have something they can be measured against. If you have the data that shows they meet or exceeds three of the five areas while the other two still have some work, they’re ready for promotion.

Look, I know it’s not a math equation, so forgive my simplification. Trying to assess if someone demonstrates sufficient “peer and organizational leadership” at the level of a senior manager is tricky business. You may have some quantifications but you’ll also have to elicit feedback from peers, leaders in other organizations, and impressions from senior leadership. It’s never going to be easy, but it can be easier and better.

What’s important is that you have a preset philosophy that you don’t need perfection from the employee across every faucet of their job, but you do need to see them be on their way to becoming very good.

We all have strengths and weaknesses. Some of us can walk into a room full of powerful people and immediately start engaging with them like we belong there. Others can build relationships with the most pain-in-the-ass stakeholders that no one else can stand. Others can “see around the corner” and identify dependencies that are months or years away and plan appropriately. But no one can do it all. If you’re waiting to see your employee become great across the board, you will wait forever. And odds are that employee isn’t going to take no for an answer forever. They’ll take their talents elsewhere, to another manager or company that isn’t such a stick in the mud and has a healthier philosophy about career progression.

Promote people when they’re mostly ready. Yes, they’ll still have some weak spots. That’s okay. A promotion doesn’t mean that work on their weak areas stops. It means that their strengths are a great asset and by moving them to the next level, both the employee and the company benefit by further unleashing those strengths. Someone who kicks ass at “delivers results” should be empowered (and compensated!) to deliver as many results as possible. Positions within the organization directly impact one’s ability to do good things, so get the person into the position where those strengths can get maximized.

There’s a valid argument for wanting to see someone in action at the next level for some time. And there are some jumps, like from IC to people manager, that a great performer may actually be terrible at. Leaders are always worried about getting the right people into the right positions in the organization. But this can be easily tested with smaller samples. Have them take on extracurricular activities for the organization, appoint them to be in charge of multi-team projects, etc. There’s no reason to hold them hostage by making them perform at the next higher level for an extended period of time.

What you can do to help

Depending on where you lie in the organization, here’s how I think you can help your company move to a better promotion process like described above.

Head of X: You’re responsible for setting the standards at each level and position of your org. Doing this right is a cannot-fail responsibility. You can delegate parts of it like massaging descriptions, calibrating expectations, etc. But you own this. Your organization’s culture and climate will live or die by the ability to help everyone know what right looks like and how they can align their interests with the company’s by delivering great performance and getting rewarded as a result. So plant a flag in the ground. Make it clear that promotions are the result of being mostly ready for the next level, being on the upper half of the steep slope of the S-curve before you plateau. Not before, but not after either.

Senior leader of X: You’re probably part of the inner circle, the cabal of leaders that Head of X uses as their brain trust and guidon bearers. If there aren’t standards and expectations set, you better be pushing hard for them. Volunteer to get the process started and steal everything you can from other companies and organizations that make their standards public. If there are standards, treat their curation as a sacred duty. Help spread understanding across the organization on what right looks like and what mostly ready looks like.

IC / Junior leader of X: If you’re at all uncertain of what right looks like, push your management team to spell it out for you and your peers. Keep pushing until satisfied. Recognizes that evaluation performance will always be qualitative and fuzzy, but that there can still be a rubric and standards for assessing.

Literally everyone: Okay, I’m going to yell a bit, so stand back.

inhale

YOU ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR YOUR CAREER. DO NOT GIVE AWAY YOUR AGENCY BY EXPECTING OTHERS TO “GIVE” YOU A PROMOTION. THAT PROMOTION IS YOURS, YOU EARNED IT. YOU TAKE IT, YOU DON’T GET IT.

exhale

The promotion process will never be perfect. No math equation can decide if a person is mostly ready for the next level. If you’re evaluating two people for a potential promotion across five areas, with Person A great at 2 areas, okay at 2, and bad at 1, while Person B is great at 3 areas but bad at 2, are they both mostly ready? Just A but not B? Neither? That’s why we pay senior leaders those big salaries, so they can figure out these sorts of things with nuance and diligence.

We humans are flawed things and as a result, so are our processes. But we can be better. By building a strong foundation through a clear promotion process, philosophy, and standards, we can demystify a lot. It’s the opacity of such an important process that causes so much heartburn to everyone involved. Transparency breeds trust and buy-in, which leads to better retention, better culture, and better business outcomes. A good promotion process, philosophy, and standards isn’t just the right thing to do to take care of your people. It’s how you build a great business too.