The Quest to Define Supply Chain Visibility (Part Duex)

This edition of Rough Terrain is brought to you by Cometeer coffee. It’s the best coffee in the world. I’ve doubled my subscription because SOMEONE (glares furiously at the wife) keeps drinking it. Make your first purchase using this link and we both get $25 off!

Well, the last edition of Rough Terrain certainly grew wings! Many thanks to the folks who shared it around the interwebz and especially to Flexport for not firing me promoting it. Someone said my last article was like “XKCD of Supply Chain” which is just about the highest praise I can imagine. Clearly, I’ve touched a nerve as I continue down my hero’s journey of becoming the resident shit poster of Logistics Tech. Since I’m ever eager to quell my neurotic imposter syndrome, I’m going to give the people more of what they want!

Let’s get onto Part Deux of The Quest to Define Supply Chain Visibility!

Recap

If you didn’t read Part 1 (or have forgotten), here’s a rapid summary:

Supply chains are a never-ending cycle that is generally broken into seven segments: forecast, purchase, produce, move, receive, distribute, and sell

In a hypothetical scenario of a grocery store that sells coconuts, the supply chain necessary to get those coconuts to the store is complex, with many moving pieces and parties involved

No one is big enough to control all aspects of their supply chain. Even the titans of consumer goods like Walmart and Amazon rely on others for help. In fact, there’s a direct correlation between the size of the company and the complexity of its supply chain. The more things sold, the more parties involved in the supplying of those things!

The complexity and multi-party nature of supply chains make it super tough to know what is happening. And if you don’t know what’s happening in your supply chain, you’re going to have a bad time, m’kay. Any amount of inventory that is somewhere in a supply chain besides where it can get sold is unproductive inventory and that’s tantamount to lighting cash on fire. So you probably need to know about that, right?

Thus, companies all desire supply chain visibility, which lets them know what the hell is going on. Supply chain visibility has three components: Observe, Share, and Action

The first component, Observe, has two sub-components: Observing the location of the thing you’re concerned about and observing its status.

All caught up? Good, let’s get to the 2nd component, Share!

Sharing

Originally, I only drew Observe and Action as the components of supply chain visibility. It seemed unnecessary, and even redundant, to say that one should share the information they’ve observed. Sharing is caring, right?

hahahaha, it’s almost like I haven’t worked in this industry for more than a day

(collapses into the fetal position, weeping)

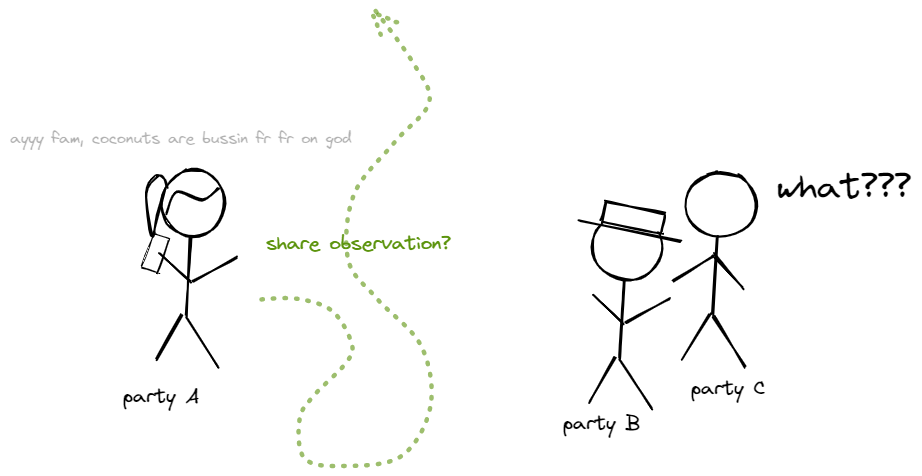

Sharing is the distributing of Observations (consisting of location + status) made on the supply chain to relevant parties. Party A (coconut farmer) observes a thing (coconuts are growing on schedule) and tells Parties B (distributor) and Party C (grocery store). Party A is the one who made the Observation, while B and C are relevant parties who need that Observation for their supply chain visibility. Thus Party A transmits it over to B and C to keep them informed. Such a straightforward thing that you’d think it would be easy. Super easy. Barely an inconvenience.

Yet it’s where things get royally messed up. Maybe not so easy after all.

In Part 1, I remarked on how Observations can go wrong. Maybe observations aren’t getting made or not made frequently enough or not made accurately. But things going wrong in the Observe component pales in comparison to the things going wrong in the Share component. This is where the wheels really come off for supply chain visibility. Here there be dragons.

Why? How hard could it be to distribute some information to other parties who want it? Aren’t the incentives all aligned? The distributor and grocery store definitely want those observations from the coconut farmer.

Stay with me as I walk you through an analogy of what Sharing is and why the supply chain industry sucks at it. Trust me, it will make sense.

Or it won’t, who knows, this newsletter is obviously not a professional endeavor.

Last week was my son’s final Little League baseball game of the season. We had a pizza party afterward where we took a team photo. There were 14 kids in the photo and 14 sets of parents with their phones taking pictures. This struck me as a perfect analogy of the issues between Observation and Sharing as it applies to supply chain visibility. Mostly because of how utterly absurd the situation was.

Observing the team only took one phone. Any single parent could have taken the picture while the rest of us hung out. While having ~28 phones take a photo might improve the observation of the kids (additional angles? better lighting?), it’s probably only a slight improvement, if at all, from having just a single camera do it. I don’t think a single parent thought to themselves “I better take a picture in addition to the others because we need the picture from another angle / better lighting / whatever”.

So why did everyone decide to make so many unnecessary replications of the same observation?

It’s not like a digital photo isn’t easy to share. It is an infinitely scalable object. A single photo can get shared with all ~7 billion people on earth at almost no cost. But if we imagine how it would have gone if only 1 parent took the photo, we can start to gather insight on why everyone took their own version:

Parent of the original photo:

Okay, I can AirDrop it to everyone. Wait, that’s only going to work if everyone has an newer iPhone model. Okay, we can text it to each other. Hold up, I don’t have most of your phone numbers saved. Okay, what about posting on Facebook? Oh, we’re not friends on Facebook, so first you need to find me and friend me. Oh, you don’t have Facebook? Okay, we can setup a WhatsApp group. Yes, you’ll have to download WhatsApp. Signal? No, I don't have that, sorry. Oh, I know, I'll email it out to the group using the same addresses that the league's newsletter goes to? Oh, you didn't sign up for that at the start of the season? There’s no lack of options to distribute the photo. Probably too many! The friction came from everyone not being able to use the same method at that point in time.

Keep in mind that this is a tiny group of people, all of whom come from the same community. We all live within a few miles of each other, our kids go to the same school, we speak the same language, etc. There aren’t cultural or institutional barriers that make it hard for us to share things with each other. The incentives align.

Despite having all the reasons necessary to share a photo with each other AND more than enough means to distribute the photo amongst ourselves, we couldn’t get it done.

What the hell is going on here?

Between being able to send the photo and being able to receive the photo lies the friction of agreeing on the method of distribution and making a connection between the relevant parties. That was just too much work vs. everyone standing up and snapping their own picture. It was the easiest option at the time. And people almost always do what’s easiest at the moment.

Across all the various means of distributing the photo, a connection is needed between sender and receiver. It’s the “friending” on Facebook, the detecting of other iPhones using AirDrop, etc. These are small things, but even small things take time and effort. If you aren’t certain that establishing a connection will have lasting use, you’d probably see no reason to invest in it. I only knew a couple of the parents, the majority were just parents of the other kids. No existing relationship nor any expectation of a future one. So no, I’m not going to add you on WhatsApp, friend you on Facebook, get your digits, etc.

Then again, the word “curmudgeon” is often used when describing me, so maybe I’m an outlier.

This is enough friction that 27 other parents would rather get up and take a picture themselves than try to get it from another parent. So their effort isn’t irrational. It’s just optimized for themselves at that point in time. They are incentivized to take the action that is easier at the moment (stand up, take pictures beside 27 other parents) than take the action that is higher cost/uncertain lasting value (establish a connection with the original pic taker, hope they send the picture, wait for the picture to arrive, hope it’s good quality, etc).

If a bunch of incentivized parents from the same town can’t get on the same page to share something as effortlessly transmittable as a digital photo, you can start to imagine just how much of a clusterfuck sharing observations of a supply chain might be.

In the example of the grocery store that sells coconuts, there’s way more friction than in my story of taking a picture. That friction causes the incentives of the involved parties to not seek connectivity between each other, degrading the interest and ability to share.

I’ve grouped the frictions into 2 root causes based off my experiences:

1. Fragmentation

First, there’s significant friction due to the fragmented nature of supply chains. The grocery does not grow the coconuts they sell. They buy them from a coconut farmer halfway across the world. And the company they actually transact with to buy the coconuts from isn’t the farmer, but a distributor that works with the actual growers. If you think a grumpy curmudgeon such as myself doesn’t try hard to make connections with my own neighbors, you can imagine why a coconut farmer on the other side of the world from the grocery store they’ll never meet, and probably doesn’t even know about, won’t go out of their way to make sure the observation of their coconuts is made available to the store.

No matter how well-intentioned all these parties are, there will never be a perfect alignment of interests across all of them. Like the classic children’s game of “telephone”, the message gets a little distorted every time it passes from one party to another. It’s Metcalfe’s Law, but not every participant is capable (or interested) in building a connection with every other participant.

I recently toured a cargo terminal at an airport. The ground handlers at the terminal had useful data relevant to my company’s shipments. Yet they didn’t share them with us. Why? Because we didn’t directly work with them. Between them and us was the air carrier that we had booked the shipment with. The ground handlers at the terminal were like a sub-contracted vendor. Nice folks, did great work, but since the air carrier wasn’t pressing them to share the observations with us, they weren’t incentivized to. My company is a step removed from them and not their customer, so our interests are considered but not necessarily prioritized.

Don’t worry, that’s all fixed. But the example is everywhere in this industry.

Now, I’ve largely picked on all the parties external to the grocery store for not having their shit together. And it’s true, many of them don’t. But I also want to cast a critical eye on the grocery store as well. Don’t assume that just because the grocery store is at the center of the supply chain diagram it is a well-oiled machine. At any company of moderate size or more, the internal coordination between the teams responsible for different segments of the corporation’s supply chain (forecast, purchase, move, receive, etc.) can be wildly uncoordinated. The folks managing the warehouse don’t talk to the folks generating next year’s forecast who don’t talk to the folks scheduling capacity across their trucking partners who don’t talk to….

Metcalfe’s Law is a son of a bitch, huh?

Because supply chains are so complex and involve so many parties (both external to the company and internal to it), there’s a high cost to getting all those parties on the same page to share with each other. And even if parties are incentivized and agree to share with each and actually do it, that opens the next can of worms…

2. Methods of Sharing

The actual means of distributing observations is a big friction point. Like, a BIG one. The supply chain industry is.. ahem… adopting modern technologies at a cautious pace. Only 1.2% of bills of lading were digitized in 2021 (source). The dominant software in this industry is Excel and much work remains in paper form only. For our grocery store, an email from the coconut farmer may be perfectly sufficient. I don’t know jack about coconut production but it’s probably something that you can get a weekly email about and call it good for Observation and Sharing components of supply chain visibility. But for companies with larger supply chains to manage, emails and Excel files ain’t gonna cut it, boss.

If you have an Excel on your computer with a title like “Final_Version_v2_Edits_Master_seriouslyguysthisisthelastversionIsweartoGod” you understand why. The sharing of observations for supply chains quickly surpasses the capabilities of software like Excel in terms of storing historical records, collaboration, security, control, data validation, and more.

While there are plenty of broadly adopted technologies to transmit photos of a kid’s baseball team (Facebook, email, text, WhatsApp, etc.), the world of supply chain lacks similar centralized rails for transmitting across parties. Folks tend to do their own thing (see issue above about Fragmentation). While there are some standards, they aren’t broadly followed and only cover segments of a supply chain (example for the Move segment).

This lack of common methods of transmission between parties raises the cost of sharing. If you’re a coconut farmer with a big crop that is going to a major grocery chain, you’re probably forced into transmitting updates about the coconuts via API or EDI to the grocery chain’s supply chain software system. That’s a big pain in the ass for a farmer whose day-to-day job doesn’t involve API integrations. Conversely, if the farmer is the one in the position to dictate how the observations get shared, the grocery store is having to use its employees to upload an excel file into their system while probably doing a bunch of normalization and translation of the data.

This literally increases the cost of doing business. If the grocery store is hiring a clerk to do a bunch of manual uploads of Excel files from its various suppliers, (a) that job sucks and (b) there’s another salaried employee on the books, increasing operating costs which is probably passed onto the customer in the form of more expensive coconuts. Same kind of situation for the farmer who has to start transmitting updates via API.

This is the same inability of all the parents to get on the same platform for sharing the photo of the kid’s baseball team. In that example, the friction arose from too many options and the lack of any one option being universally adopted. In the world of supply chain, it’s generally a problem of a lack of options in the first place, forcing companies to fit square pegs (excel files) into round holes (TMS, ERP, WMS, and other supply chain software).

Get on the same page people, am I right???

Wrapping things up

There are a number of companies trying to fix this - make it painless to share observations with the relevant parties across a supply chain. Lots of talk about pipes, IoT, rails, blockchains, and other buzzwords. I commend all of them, as it’s something the industry desperately needs. But we’re talking about an industry so large and so complex it boggles the mind. Don’t let yourself get fooled by any company promising silver bullets to what ails ya.

Underneath the software built by any supply chain technology company lies the people who use it. And these people have different incentives depending on where they sit. No amount of nifty, seamless technology platform can overcome a misalignment of incentives. What problems the farmer needs to solve may not overlap with the problems a clerk in the back office of a grocery store on the other end of the world has.

The battle to align incentives and lower the cost of sharing observations is a long one and must be fought by each company as it manages its supply chain. My hope is that companies with influence in the industry (STARES AT SPECIFIC READERS OF THIS NEWSLETTER) can help drive the adoption of standards. This lowers the cost and friction of transmitting between parties as the industry gravitates to specific methods (like how we have great options for sharing a digital photo). The more the industry settles on specific norms, the easier it becomes for the smaller players like our grocery store.

I do love a good fight.

If you enjoyed this edition of Rough Terrain, maybe subscribe? How else will you read the thrilling conclusion on my treatise about Supply Chain Visibility as I deep dive into the Share component? Be sure to pick up some coffee on your way out.

Perfect analogies for the imperfect reality that is, and has been, SCV for the past 3 decades. Bravo!

Hey Cy,

I am curious what - if any - lessons there are to be learned from the standardization of the shipping container?

Just took a look at DCSA and it looks like that is the foundation or inspiration for what they are working on.

Thanks for sharing,

Taylor