The quest to define supply chain visibility

“supply chain visibility, how does it even work?” - Insane Clown Posse (probably)

This edition of Rough Terrain is brought to you by Cometeer coffee. It’s the best coffee in the world. I’ve doubled my subscription because SOMEONE in my house (glares furiously at the wife) keeps drinking it. Make your first purchase using this link and we both get $25 off!

Since my blog has like 50 readers, I’m assuming that you all know what I do for my day job. I’m the Commercial Product Lead for Visibility at Flexport. We try to answer the fundamental questions “where’s my stuff?”, “when will it get here?”, and “how’s it doing?” for the tens of thousands of shipments Flexport moves across the world on behalf of its clients. Answering those questions is not easy! I’m going to use this blog post to explore just one of those reasons, which is that when you get 2 or more supply chain folks in a room, they can’t for the life of them agree on what supply chain visibility even means. It apparently means everything. Which is another way of saying it means nothing.

Confused? Me too, and this is my day job.

There is so, so, so (so so so) much about supply chains and logistics that I don’t know. It’s a leviathan of an industry, with each segment so complex that one could dedicate their life to mastering it while never learning much about the other segments. I know very little about my own segment (freight forwarding and international trade) and I know almost nothing about all the other segments.

But I’m never one to let a little thing like ignorance get between me and loudly voicing my opinions.

I’m my own biggest critic, so in an effort to get better at my job, I’m using my personal blog to help connect some of the dots on my answering these questions (“where’s my stuff?”) is so hard.

I suspect what it means to me over in my little corner of the supply chain universe might hold up and apply elsewhere. And maybe, just maybe, if a few more people agree with me, we can build some momentum towards building a common operating picture of what it is. We’ll be speaking the same language. And in this industry, having a mutually agreed-upon definition of anything is gold.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t take this time to broadcast that I’m hiring. So if this article tickles your fancy and you’re thinking you want in on this action, I suggest browsing Flexport’s job board and looking for all the openings that have Visibility in the title then holla at ya boy.

Use code “TMOTRIWQTGPIEHOAIWFTTTGOVIIGTJ” (the manager of this role is without question the greatest person I’ve ever heard of and I would follow them to the gates of Valhalla if I got this job) to get to the top of the waitlist!

To reiterate the disclaimer at the top - everything on this blog is my own opinion and does not represent my employer. Please don’t fire me Carol, kthanksbye.

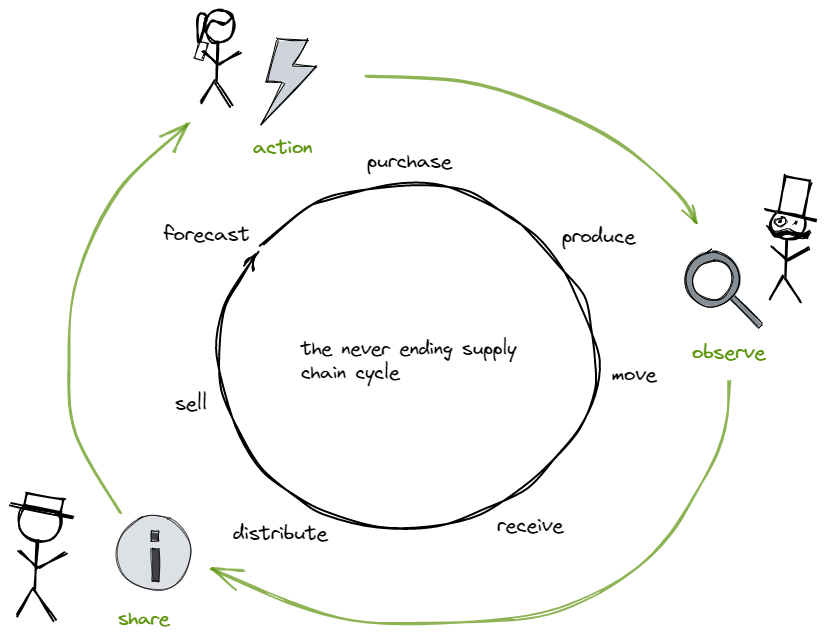

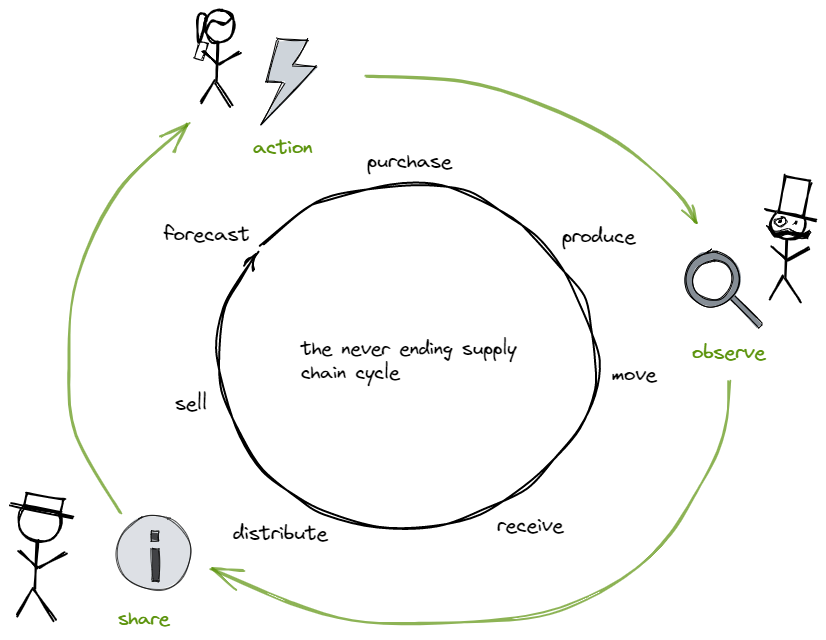

Behold, my visualization of supply chain visibility. Bow before its brilliance.

The inner circle represents a typical supply chain. It’s a never-ending cycle of knowing what stuff to get, how much stuff to get, getting it, making use of it, then doing it all over again (unless the company goes out of business). I simplify it into seven steps: Forecast, Purchase, Produce, Move, Receive, Distribute, and Sell.

The outer circle (in green) represents supply chain visibility. I posit that there are three major parts of supply chain visibility: Observe, Share, and Action. We’ll come back to these in a bit.

First, let’s chat about the inner circle. We must understand that before we can understand why it’s so hard to maintain visibility on it.

Consider the coconut (the palms and the leaves, the island gives us what we need. Moana is the GOAT Disney Princess, fight me if you disagree). If a grocery store sells coconuts, it must have a supply chain for said coconuts. Painting with a very broad brushstroke, the grocery store has some key steps to ensure it has coconuts:

Forecast: It has an opinion on just how many coconuts it needs. A smart grocery store will take into account a variety of factors, like historical sales, seasonality of those sales, shrinkage, the impact of coconuts sales on like items (do people buy fewer mangos?), and lots of other stuff. They figure out how many coconuts they want to have in the store for a given period of time.

Purchase: They take their number of desired coconuts and find a supplier that can provide them with that many coconuts (hopefully). An agreement is struck and the grocery store purchases the coconuts.

Produce: That supplier may or may not have the coconuts ready to go. Let’s assume that there’s less than the desired quantity ready to give to the grocery store, so the supplier has to make (grow) the coconuts. Perhaps by themselves, perhaps they have their own suppliers (supply chains within supply chains!)

Move: Okay, the coconuts are ready. Time to get them to the grocery store. Oh wait, the grocery store is like 5000 miles away from where the coconuts were grown and there’s an ocean in the way. Neither coconut grower nor grocery store has their own ships and trucks to move it. Time to employ a few other companies to get those coconuts where they need to go! That’s where Flexport and other logistic service providers come into play. And the many carriers that do the moving of the goods across plane, train, ship, truck, barge, camel, whatever.

Receive: ok, coconuts have arrived. Now that the inventory is finally in the grocery store’s hands, they have to sort it, verify they got what they ordered, reconcile their ledger, etc.

Distribute: Now the grocery store has to split their newly acquired inventory, putting some up front for customers and some in the back into short-term storage (since there isn’t enough space to put all the coconuts out front).

Sell: It’s the grocery store’s favorite step, actually converting all the inventory into sales! Up to this point, they have spent a LOT of money purchasing the coconuts, waiting for those coconuts to be grown, and moving the coconuts to their store. Because there’s a time value to money, they’ve had a lot of cash locked up in those coconuts despite not actually having the coconuts in the store! That’s unproductive inventory, something every Chief Financial Officer loses sleep over. So you better believe they want those coconuts to get bought by customers. If they aren’t, there’s a big problem. Hope those forecasts were correct!

Do it again: As the coconut inventory goes down thanks to sales, it’s time to place the next order with the suppliers. Does everything stay the same? Buy more or less this time? From the same supplier? Do we order smaller amounts so they ship more often? Do we keep the same freight forwarder in charge of moving them or find someone promising faster/cheaper rates?

The questions never stop. That’s because the supply chain never stops. The wheel in the sky keeps on turning.

I’m sure I’ve missed like 10,000 things and some Wharton-educated supply chain nerd who’s worked at Cisco for 30 years will be all like “AcKChyuAllY” but whatever, this is my blog and I’ll be as wrong as I want to be.

This framework is scalable and extendable. Even a company like Costco or Home Depot, with 1000x the quantities of stuff that this grocery store has, has these same steps in their supply chain. How they do it is incomprehensible to me. Just the Receive step for a company like Costco requires an incredible amount of orchestration. But the same goes for tiny Mom & Pop stores that never ship any international freight - they’ve still got to find suppliers for their products, get them moved to their store somehow, etc. Same cycle, same framework, just different scale.

And what about the companies that play a role in enabling the supply chain of the grocery store? Like the truck that drove the coconuts to the grocery store. That trucking company has its own supply chain to manage to ensure it can sell its service (moving stuff). But from the perspective of the grocery store, the trucking company provides a critical asset (the truck) and service (driving the truck to someplace, loading it with the coconuts, driving it to the grocery store).

Perspective is a really big factor at play when it comes to supply chain visibility. Remember that.

So we’ve got supply chains within other supply chains (Coconut producers sub-contracting the growing of coconuts) and supply chains tangential to other supply chains (trucking company selling its service to the grocery store). It boggles the mind to try and comprehend the complexities and interconnectedness. Use my secret trick instead - don’t bother. Sit back and watch the glorious chaos.

That’s all well and good. Huzzah for the grocery store, they got their beloved coconuts.

Except maybe they didn’t? Or maybe they did, but not the agreed-upon amount? Or it took twice as long as they expected to get them so they lost a bunch of sales and had a bunch of cash locked up in coconuts that were on the other side of the world?

If you’ve been paying attention for the past two years, you’re probably aware that because of

*gestures at everything*

supply chains haven’t been performing all that well. We had people slapping each other for the last rolls of toilet paper in 2020, big ass ships getting stuck in 2021, and now the powerhouse of European exports, Germany, can’t ship its goods because there aren’t enough nails thanks to the Ukraine/Russia war (no seriously, it’s a real thing and it’s a problem).

Those seven steps crave predictability. Most supply chains can withstand a bit of error thanks to slack in the system (coconut shipment delayed by 2 days? No biggie, the store still has enough in stock. Delayed by 2 weeks? That’s a problem, we’re losing sales). What every company craves is a well-oiled supply chain that maximizes having the right amount of stuff for the shortest amount of time necessary. Get it wrong and you’re lighting money on fire.

Every company cares deeply about understanding the health of its supply chain. Where are the bottlenecks that are going to slow things down? Where’s the inefficiency and waste in the system? Every VP of Supply Chain sleeps with a copy of Goldratt’s The Goal by their nightstand. It’s no surprise that an optimized supply chain is considered a competitive advantage.

To even try to answer those questions, you’ve got to be able to know what the hell is happening in your supply chain. You need to be able to watch the system. The entire system. It’s not enough that the grocery store monitors how many coconuts it has in the store. That’s the easy part. They must have insight on how far along those coconuts getting grown are, where exactly the shipment of coconuts is that is on its way to the store, if the coconuts got hung up by the FDA at the border because of a paperwork issue, how many coconuts they will receive vs what they initially ordered, etc. The supply chain is a circle, not a line. If something before or after the sale gets screwy, there’s a ripple effect.

Problem is, all those questions can’t be answered by the grocery store. The coconut producer can answer (maybe) the question about the state of the current crop. And the grocery store’s freight forwarder can answer (maybe) the questions about where the shipment of coconuts is and what’s being done by the FDA. This raises some serious questions:

Who (if anyone) is watching each segment of the company’s supply chain?

If someone is watching (big if), do they actually know what’s going on?

If they know what’s going on, do they share it?

If they share it, is it well understood by others?

If it’s understood, is anything done about it?

Welcome to the wonderful world of supply chain visibility, my friends. Come on in, the water is just (checks temperature), boiling hot.

Step 1 - Observe

Watching the entire system is really, really tough because it’s so complex. In the simplified example of the grocery store that bought coconuts, you can see how many players get involved. The grocery store doesn’t have cameras set up in the coconut tree groves to watch them grow. It doesn’t have an employee at the port who can confirm if their container full of coconuts was loaded on a ship. Other companies have been employed for that part of the supply chain.

The industry is incredibly piecemeal and fragmented. This means that lots of different parties, with different incentives, have to observe the activity that is relevant to a specific supply chain like a grocery store.

This is the first step of supply chain visibility - observation. The watching of activities in a supply chain. Having access to the information that helps answer the questions like “where’s my stuff?”, “how’s it doing?”, and so on. If parts of a company’s supply chain are not observable, they are operating in the dark, having to trust that things are going according to plan.

Remember how I said it’s all a mind-boggling ecosystem of barely-organized chaos?

And how most companies’ supply chains have a little bit of slack in them but not much?

Then you can probably appreciate that having parts of your supply chain “run dark” or be “black boxes” is not good. Not good at all.

Gaining observability into each step of the supply chain is the must-do first part of supply chain visibility. If you cannot observe a thing, you’re certainly in no position to do something about that thing. You’ve got to be able to shine a light on any part of your supply chain.

Basically, you need the Eye of Sauron.

no joke, I’ve lobbied to make this my team’s logo

This is my bread and butter at Flexport - obtaining observability into things. Namely, big metal things, like container vessels, airplanes, and 40ft boxes full of stuff. But while I care about certain things that fit in the Move section of the supply chain cycle, observability is critical in every single segment.

Observability has two sub-components: Location and Status/Attributes

Location: Where is the thing? Where will it go next? Of the two components, this is the more straightforward. It’s pretty easy to know the location of a NeoPanamax container ship. It’s less easy but still doable to know where that ship will go in the not-to-distant future. From the perspective of our grocery store, they don’t care about the ship. They just care about their coconuts, which happen to be stored in boxes, assembled on pallets, and stuffed into a 40ft metal shipping container that is on that ship. So they’ll take the location of the ship as an adequate substitute for their coconuts for a time.

Status/Attributes: How is it doing? Is everything okay? This is the harder component to get answers to. Why? Because “how are things doing” is far more subjective than “where are the things”. You first must have an opinion on what the status should be and if you find out that it is in fact NOT the current status, then you have the answer to your question. In my neck of the woods, this is answering questions like “has the shipment cleared customs?”, “is it available for pickup?”, “will it still arrive on the day we first said it would?”. Obtaining the latitude and longitude of things isn’t particularly difficult. Translating the implications of the thing’s location is.

My examples fit within the Move step of the supply chain but are equally applicable in the other steps. In the Produce phase, the coconuts don’t move. But their status is not static - either they are growing according to schedule, or there’s crop rot that threatens the production, or a whole host of problems. In the Sell Phase, Location may be where they are within the grocery store (end cap, produce section, etc.) while status may be current inventory levels, the price we’re selling them at, etc. Location and Status are intentionally broad categories so they can be formed to fit the requirements of each step. But these two categories should capture what’s needed to “see” the products in any segment of the supply chain.

Look at this diagram again.

It’s a circle. There is no end. That’s why the phrase “end-to-end visibility” makes me cringe. Things only end from the perspective of someone responsible for a segment. From my point of view as a freight forwarder, things end when I deliver the goods to our shipper’s door. While that’s the end of the shipment, it’s not the end of the supply chain. That shipment becomes inventory in a warehouse so it can get sold so it can become cash so it can be reinvested into new purchases so it can….

Perspective in this industry matters, remember? If you see “end to end”, that’s marketing material, not capabilities. Nobody has end-to-end supply chain visibility unless it’s the company whose supply chain we’re talking about. And I’d wager that only a few of the very biggest consumer and industrial goods companies have the means to achieve it.

Writing this blog post has given me a greater appreciation for how critical it is to obtain and maintain observability on a supply chain. But what happens when you get that observation set up? Well, you need to share it and take action on what you share. But you’ll have to tune in for my next newsletter to find out what that all means. Guess you better subscribe so you don’t miss it, huh? Oh, and go buy some coffee!

This is a pretty good explanation of the challenges encountered in operating any kind of supply chain Cy. Well done! Hopefully it will get some serious exposure and enough patient readers who will read it through to the end. Your last comments are particularly spot on... For years I have been telling anyone who will listen, that almost no companies really have full end to end visibility (not forgetting the return/repair cycle), due to the complexity of global trade - yes, i need to get out more.