The Dangers of “Heroic Leadership”

Why being the hero of your organization may very well end up crippling them and what to do instead

Let me tell you about Iron Mike. Iron Mike is a famous statue of an American soldier you can find at various US military installations and battlefields across the world. He is a symbol of toughness, resilience, courage, and pretty much all those characteristics you’d want out of a military leader. Captain America, made mortal and in-reach to the common man. He serves to inspire others to be like him - a guy who stares down danger and doesn’t blink. A guy who ain’t afraid of getting his hands dirty and doesn’t know the word quit. And Iron Mike will always be in the thick of the action because that’s where the presence of a strong leader can turn the tide. Iron Mike shows us that a good leader always “leads from the front”. He’s at the tip of the spear, leading by example and showing how he’s always willing to risk himself first before they’d risk anyone else’s life. His catch phrase is “follow me!” because he’s always in front of everyone else, never behind them. You follow him because you know that whatever he’s doing has got to be the most important thing to win the fight.

I’m going to summarize the spirit and principles that Iron Mike represents as “Hero Leadership”. The sort of leadership you want to read about or see in the movie. The sort that makes you proud to be Gawd Damn ‘Murican!

As it turns out though, Hero Leadership is not a good way to lead an organization for any sustained amount of time. It certainly has its place in the pantheon of leadership styles but I’ve seen it too often become the style de jour of many leaders who leave a wake of under-developed or outright crippled organizations in their wake. I’m speaking from the experience of having those types of leaders and BEING that type of leader.

Before I expand on why I’m making such a heretical statement, let me set the stage a bit.

As a cadet at West Point, Iron Mike and his Hero Leadership was everywhere. We lived, ate, slept, and breathed the ideas that Iron Mike represented. It was the gospel we sang every day. Leading from the front was a sacrosanct principle pounded into the heads of every cadet. We’d attend leadership lectures from colonels and generals who’d preach the importance of always being an example of excellence, always showing the troops how you’ll suffer along side them, and so on. You were swept up in the spirit and fervor expressed by these experienced leaders, longing desperately to be just like them. You dreamt about when it would be your turn to be Iron Mike.

From West Point’s perspective, this makes a lot of sense. It’s the preeminent leadership factory in the world (Stay in your corner USNA and watch your shitty James Franco movie on repeat, you copy-cat wannabes). So distilling an incredibly complex thing like how to lead other adults in combat into tangible principles and standards so thousands of 18 to 22 year-olds can learn them requires simplification and making things black-and-white. And this great! Young eager minds shaped so they embrace the principles of leadership the US Army finds to be best. It’s in the best interests of the nation for this process to succeed.

This principle was further reinforced to me at Ranger School. At Ranger School, no detail is too small for a leader and when it’s time to lead a raid or ambush, you bet your ass that if you’re in a leadership position, you’re at the front of the attack. They taught us that if we wanted someone to move from one position to another (maybe shifting which tree they were behind), we should physically grab them by the back of their collar and pull them to the new location. Bare in mind that these were grown ass men at one the world’s toughest military schools, so you might think this type of “I know what’s right and I’m going to do it myself” leadership would not be necessary. But even at the school famous for teaching you how to fight tigers underwater, this was the style of leadership taught. Again, the spirit of Iron Mike - leadership through exerting your will through the organization to make things right, down to physically repositioning other people. Hero Leadership.

Basically, the military preaches that to be a good leader, you need to be King Theoden - leading the cavalry charge from the front, setting a glorious example to the rest of the organization (ideally screaming DEATH at the top of your lungs while plunging your spear into the chest of an orc). Go ahead, you know you want to go watch the greatest scene in cinema ever now that I mentioned it. I may have watched it like 15 times after going to Youtube to get that link.

I can think of no better example of Hero Leadership in current times then-Brigadier General Mattis (later Secretary of Defense Mattis) when he was Task Force 58 commander during the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. Mattis famously lead the Marine convoy into Khanadar, occupying the first vehicle in the convoy. His behavior was 100% Iron Mike - if there was going to be shooting, it should be him that would first be shot. If there were land mines, his vehicle should absorb the first blow. This way, perhaps he could take the injury or death rather than one of his men. That’s the kind of Heroic Leadership that made Mattis the legend he is and why any Marine will gladly take a bullet for him to this day (and why there’s hilarious memes of him like the one below and also why I’ll likely get poorly-spelled death threats written in crayon for daring to besmirch St. Mattis.)

Now, imagine being the poor son of a bitch who takes command of a unit after Mattis leaves it. Quite a pair of boots you have to slip into.

And there in lies a problem - if that’s what Heroic Leadership is in the eyes of a unit, how could you as the person replacing Mattis hope to match it? Let along top it? Does every unit commander of every unit Mattis ever commanded suffer in his wake because they are facing an impossible standard? Does the unit Mattis leaves continue to succeed in the absence of such an undeniable force of nature? Or does the departure of the Alpha Giga-Chad Iron Mike create a hole that’s too large to fill?

It’s these thoughts that have led me to start to break ranks from the Church of Iron Mike.

Why do I call it potentially dangerous leadership? Because organizations need to outlast their leaders. The mark of a great leader is that the organization they led continues to get better AFTER they’ve departed. That shows the leader has effectively matured and professionalized the organization to the point it is not just self sustaining, but self improving. It has become a flywheel that continues to accelerate. But if the organization is subject to Hero Leadership, where the nexus of decision making, authority, and energy lies on the shoulders of one Iron Mike-type, what happens when the next leader isn’t an Iron Mike? Does the organization crumble because it was so dependent on Hero Leadership and it’s no longer getting it’s fix? Or does the presence of a less competent leader not make much of a difference because the organization has grown beyond the point of any single person being a major factor in its success?

This concept of organizations outlasting any single leader, even a force of nature like General Mattis, is a concept I learned from my favorite book on leadership, Turn Around The Ship by David Marquet (yes, a leadership book from a Navy guy, my opinion on USNA remains unchanged). This book really opened my eyes to how little I had thought about why my style of leadership was the way it was. Marquet impressed upon me two critical things:

Great leaders create the conditions for organizations to succeed well after they depart

To accomplish #1, authority needs to flow to information, not the other way around (which is how most organizations work)

Revisiting Mattis for a moment. I’m certain none of his units imploded upon his departure. That’s because the US Military has centuries of experience in building and sustaining large organizations. There’s probably no institution better positioned to be able to weather having either a great leader or a poor leader in charge of a unit yet still accomplish its mission. But this is a singularly unique situation. The US Military invests BILLIONS into professional education of its officers and enlisted service members, molding them into leaders. I wasn’t joking when calling West Point a “leadership factory”, as that’s what it does - it produces a bumper crop of ~1000 new officers for the US Army every year, steeped in the culture, norms, and processes of the same institution that gave the nation Grant, Sherman, Patton, and Eisenhower.

Let’s say that Mattis did actually get shot while in the lead vehicle during the invasion of Afghanistan. It would take all of 1 second for his 2nd-in-command to assume the mantle and continue leading the task force. No normal company could do something like that. If some executive suddenly departs your company, maybe there’s a clear successor already identified and maybe that executive had done a good job preparing their organization to succeed without them. But odds are neither is true.

Think any private or public company has anything remotely as developed for training and educating their leaders? Not a chance! Maybe there’s a bi-annual 2-hour training by some Learning and Development team that instructs managers how to be better listeners or some thing like that. The quality and quantity of instruction on how to be good at leadership in corporate settings is but a tiny, pale shadow to what the US military provides its members.

Which only heightens the impact that a single leader can have in a company, either negatively or positively. If the CEO or VP of Sales or Head of Product or whomever is a force of nature that valiantly leads their organization like a corporate Iron Mike then one day resigns, there’s going to be a giant hole felt by the entire company.

My Own Lessons Learned

I write all this with a fair amount of personal experience. Over my career, I’ve left teams that imploded shortly after my departure because they were unable to survive my absence. I failed to up-level my direct reports, teaching them to rely on me instead of rely on themselves. I know a part of me relished the feeling of others needing me and the reward for my selfishness was organizations and careers stumbling because I was the quintessential Heroic Leader. I failed to understand just how much institutional scaffolding surrounded me while serving in the Army that would ensure any unit I led continued to succeed long after my departure and that there was no such support in the civilian world.

There’s a term I’ve invented (or heard/read somewhere else and am now claiming I thought of) called “Leadership Gravity”. Leadership Gravity is when someone’s presence within the organization is so impactful that they generate a psychological “pull” towards them. Others are naturally drawn to them. Iron Mikes exert Leadership Gravity because they’re so confident in themselves and their mission. Clearly Mattis has Leadership Gravity in spades. Title and seniority can definitely give someone greater amount of gravity, but I’ve seen relatively junior people shift the energy of large rooms towards them because they have this characteristic. I’m not sure what this effect really is, but I know that it is a very real thing.

I know this because I have it. Not a particularly humble thing to say, I get it. In my defense, this is an article about how Heroic Leadership can be a very bad thing, so take that into account before you roll your eyes too hard. But I am aware of how I’m able to shift the tone and energy of rooms I enter and how people have a tendency to look to me for decisions or reinforcement.

That’s why I’m hyper sensitive to the dangers of being an Iron Mike and practicing Heroic Leadership. Because it’s very easy for me to do it and I’ve seen the damage it can do.

Good organizations out last good leaders. The mark of a good leader is that the organization keeps getting better after they’ve left. If it falls apart after the leader’s departure, you’ve got a clear example of Hero Leadership.

What’s the alternative?

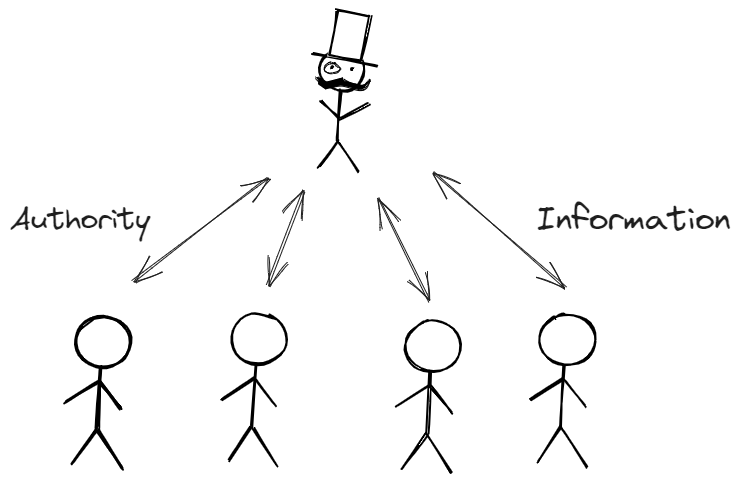

I’m still figuring it out, but Marquet gives a lot of tools and resources in his book. He calls it Intent-based leadership, I’m toying with the idea of “leadership from within”. Where instead of leading your organization in a top-down manner with the manager up top, sucking up information and delegating out authority, the manager works to constantly remove themselves from being the chokepoint as much as possible by getting everyone else to share information and authority with each other.

In a sense, Leadership From Within is working yourself out of a job. If the leader departs the organization, the organization should continue to succeed. That’s the mark of success. It’s also very scary! There’s a sense of security that comes from being a necessity to the organization. But good leaders know there’s always more challenges to be working on, so if they don’t evolve their organization, they can never get to those additional challenges. Whereas Iron Mikes never think of working themselves out of the job because that’s abhorrent.

Much of the work for a Within Leader is around improving the flow of information. Getting people out of silos, broadcasting to the widest audience (something many people abhor doing), reconciling different interpretations of guidance, etc. If each of the arrows in my shitty diagram can be thought of as a pipe through which information flows, the leader’s job is one of a plumber - building new pipes and improving existing ones so more information and authority can flow freely and quickly.

The other major part of the job is convincing people to make decisions where they previously didn’t. This requires coaching people through the discomfort of being responsible for a lot more than they’re accustomed to, as well as at times having to move folks out who aren’t able to succeed in an environment where the don’t have someone constantly checking their work. Leadership From Within can only work if you’ve got the right kind of people who WANT ownership.

I’ve got a lot more to write about Leadership From Within, but here’s one tactic called “strategic silence” that I’ll share for the curious. This is when you deliberately do not weigh into things despite having an opinion because it’s more valuable to let an individual/team develop their level of comfort dealing with a lack of guidance and make the call themselves. I had a VP at Amazon use it on me much to my fury and his amusement. Classic “teach them how to fish” behavior that from my perspective was frustrating because had he weighed in, we could have moved faster. But he knew that we were overly reliant on him and had the answers without him having to say it to us. He was forcing us to grow by employing “strategic silence”.

When is Heroic Leadership the right way to lead?

To reiterate, I’m stating that Heroic Leadership is not a good way to lead an organization for a sustained period of time. It’s like throwing gasoline on a fire - fucking awesome for a couple of seconds but the consequences and 2nd order effects are probably not well thought out.

But in times of crisis, that’s exactly what you need. When the barbarians are at the gate, Heroic Leadership is the best form of leadership for an organization. Leading from the front to inspire others, rolling up your sleeves to pitch in, etc. But like throwing gasoline on the fire, Heroic Leadership has an extremely limited time frame where it provides value. So in situations like a massive site outage or a hostile takeover attempt, Heroic Leadership is the right call.

The danger is that you start to consider more and more things a crisis and keep defaulting to Heroic Leadership. That’s unsustainable and crippling to your organization. You stunt the growth of people under you and cause them to get addicted to always having you around.

Why is Leading From Within so hard?

Because it can sometimes feel and look like you aren’t doing much. Practicing a skill like “strategic silence” requires you to deliberately do nothing. That is extremely hard, especially for people who’ve likely found success in their career by doing the exact opposite - rushing into problems and fixing them. The thought of not responding, not weighing in, not doing it yourself can make your skin crawl. When you are Leading From Within, the type of work you do looks squishy. It can be softly guiding someone as they think through a tough decision, brokering a peace between two teams that are dependent on each other, or having regular conversations with other leaders because that relationship builds trust which in turn pays dividends as your organization and their organization start to work together more.

Furthermore, you have to be willing to stand up to scrutiny when others (who almost certainly conduct Heroic Leadership themselves) question why you’re not leading from the front. It can feel embarrassing, almost like you’ve been “caught red handed” for somehow failing to be the “right kind” of leader to your organization. Basically, peer pressure. Heroic Leaders are like The Plastics, ruling the school cafeteria with an iron fist, looking down at you for not being as great as they are.

Deep down, we’re all extremely insecure human beings, constantly trying to assess our status within the tribe. If some other leader in your organization is leading their team in a radically different way than you do, that can be seen as a threat to you and possibly mean that you’re leading incorrectly and thus less likely to succeed. So if your organization is one where Heroic Leadership is the norm, instituting a Lead From Within methodology is extremely tough. Not just because it requires shifting the mindset of your own organization, but because other leaders will see it as a threat or see you as a failure because you don’t lead like they lead.

More to come on this as I figure it out. If you made it this far, thanks for reading and please let me know what you think!